This information is for health and social care professionals.

Many people with MND experience weakness in the bulbar region, affecting muscles of the mouth, throat and tongue. This can lead to problems with speech and voice, which will affect ability to communicate.

Download our guide on speech and language in MND

Watch our training film on bulbar weakness in MND

View our information about speech for people with or affected by MND

Looking for all our resources for a specific profession or topic, for you and the people you support?

Use our Professional Information Finder

Dysarthria

Introduction

More than 80% of people with MND experience slurred, quiet or complete loss of speech (dysarthria). 25-30% of people with MND have dysarthria as a first or predominant sign in the early stage of the disease.

Once speech problems begin, communication often deteriorates so rapidly that there is little time to implement appropriate support, so timing of referral for assessment and intervention is crucial.

Deteriorating speech has a major impact on the quality of life of people with MND and their families, friends and carers.

Appropriate support from health and social care professionals, and access to augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) can help people with MND to communicate effectively for as long as possible and improve quality of life.

Causes

Physical and cognitive changes caused by MND can impact on the person’s use of speech and language for communication. Changes to physical function may mask those related to cognitive change.

Physical causes:

MND causes muscle weakness and/or spasticity, reducing range of movement in the tongue, lips, facial muscles, pharynx and larynx. People may experience:

- speech becoming slow, slurred and unclear

- a nasal quality to their speech due to incomplete closure of the soft palate

- voice that sounds strained, hoarse, low pitched and monotone

- weakened breathing causing speech to become soft and faint, or cause the person to pause for breath, disrupting the flow of speech

- difficulty making certain speech sounds, particularly consonants such as ‘p’, ‘b’, ‘t’, ‘d’, ‘k’, ‘g’

- difficulty managing saliva at the same time as speaking.

This may rapidly lead to complete loss of speech, even though limb function may be maintained for many months. This is often the case in people with bulbar onset MND, where the muscles in the throat and mouth are affected first.

Cognitive causes:

Up to 50% of people with MND experience some degree of cognitive change. This increases to 80% in the final stage of the disease. Up to 15% develop frontotemporal dementia (FTD). People may experience difficulties with executive function (the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and multitask), social cognition, behaviour and use of language. Difficulties with language may include:

- reduced verbal expression and initiation (not due to physical disability)

- problems with spelling, which will affect whether people with severe dysarthria can use word-based communication aids

- impaired naming of objects, including difficulty with finding the name of objects presented to them

- perseveration – repetition of a word, phrase, gesture or activity that is no longer appropriate to the situation

- echolalia – repeating parts of another person’s speech that have just been heard

- word-finding difficulty in conversational speech – when people pause to search for an appropriate word or name.

- semantic paraphasia – mixing up names for closely associated objects, eg ‘spoon’ instead of ‘fork’

- phonological paraphasia – where people say part of an intended word, eg pun instead of spun

- difficulties understanding complicated sentences

- impaired comprehension of words – sometimes worse for verbs than nouns.

Problems with cognition can affect the ability to use communication aids. It is important for communication difficulties to be assessed as soon as possible if cognition is affected as there may be a need for early discussions on future planning.

Impact

The psychological impact of losing speech is often overlooked. Research suggests speech loss, particularly the initial onset, has a strong impact on quality of life.This may be due to a mismatch between the person’s hopes or expectations and reality. During this initial period, it can be helpful to sensitively support the person to realign their expectations and accept the reality of their situation.

A speech and language therapist (SLT) can help the person prepare for impending changes to speech and can play a key role in setting realistic expectations, educating carers and family about anticipated change and initiating discussions about AAC.

It is essential for health and social care professionals to be aware and sensitive to the emotional and social impact of speech difficulties. People may feel embarrassed and develop a lack of confidence and self-esteem. Some people may withdraw from social situations and become increasingly isolated.

Without appropriate support to make their thoughts and wishes known, the person may lose self-determination and control over their life and their environment. The inability to communicate with others can often lead to frustration, isolation, fear and sadness.

Role of professionals

The NICE Guideline on MND stresses the value of multidisciplinary team working to achieve the best outcomes for people with MND. This type of support is associated with increased survival time and improved quality of life. Good co-ordination and communication between professionals is essential. The key professionals involved in supporting someone with dysarthria are:

Speech and language therapist (SLT)

SLTs provide treatment, support and care for people who have difficulties with communication, eating, drinking or swallowing. They aim to ensure that people with MND always have a way of communicating, regardless of their level of disability. The local SLT can carry out the initial assessment of the person with MND’s communication and swallowing needs. This may include an introduction to AAC and voice banking, as well as strategies for communication. Such strategies are important and should form a central part of the clinical intervention alongside any AAC implementation.

The SLT should consider all aspects of spoken and written communication, including use of everyday technology such as the ability to access a phone, tablet or PC for emailing, remote face-to-face communication (eg via Zoom or Skype), access to voice assisted technologies (eg via Alexa or Siri), and wider use of social media. Some of these aspects will also involve working together with an occupational therapist to find the best solution – see next heading.

Where possible, people with MND should be assessed by a therapist with specialist knowledge of MND and AAC. If this is not possible, it is essential for the assessor to have direct access to a therapist with this knowledge. The local SLT will refer the person with MND to the specialist AAC service for support if their needs cannot be met by the local SLT service and they meet the criteria. For further information, see the AAC Pathway.

Occupational therapist (OT)

Occupational therapists (OTs) can help support communication by providing appropriate seating and positioning to improve posture and mobility. They can also help identify appropriate access methods to assist a person to use AAC equipment such as switches and pointers controlled by different parts of the body.

OTs can also provide support in finding solutions to challenges faced by people affected by cognitive change or frontotemporal dementia.

The OT and SLT should work together to provide suitable environmental controls, which may be integrated into the person’s AAC device.

Orthotist

Orthotists assess for and provide supportive devices which are worn to help improve function, relieve pain and support the body. In MND, orthotists may be involved in supporting someone with their walking, hand movement or neck support. In order to effectively use certain communication aids, the person with MND may require an appropriate head support if they have neck weakness. Hand/wrist orthosis can help to keep the hand in a functional position if the person with MND experiences spasticity.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

AAC is the term used to describe methods of communication that supplement speech and writing when these are impaired. Although AAC cannot replace natural speech, it can make an important contribution to a person’s communication if introduced and supported appropriately. AAC can play a central role in the management of someone with MND. It is difficult to predict when speech problems in MND will develop, and some people experience very rapid speech deterioration once it starts.

Discussions about AAC should ideally start as early as possible to help the person become familiar with it before it plays a major role in how they communicate. Such discussions must be managed with sensitivity and should be tailored to the individual’s needs.

Using AAC can help people with MND to:

- maintain relationships

- feel less frustrated

- participate in family and community life

- be more independent

- communicate important decisions about their treatment or care.

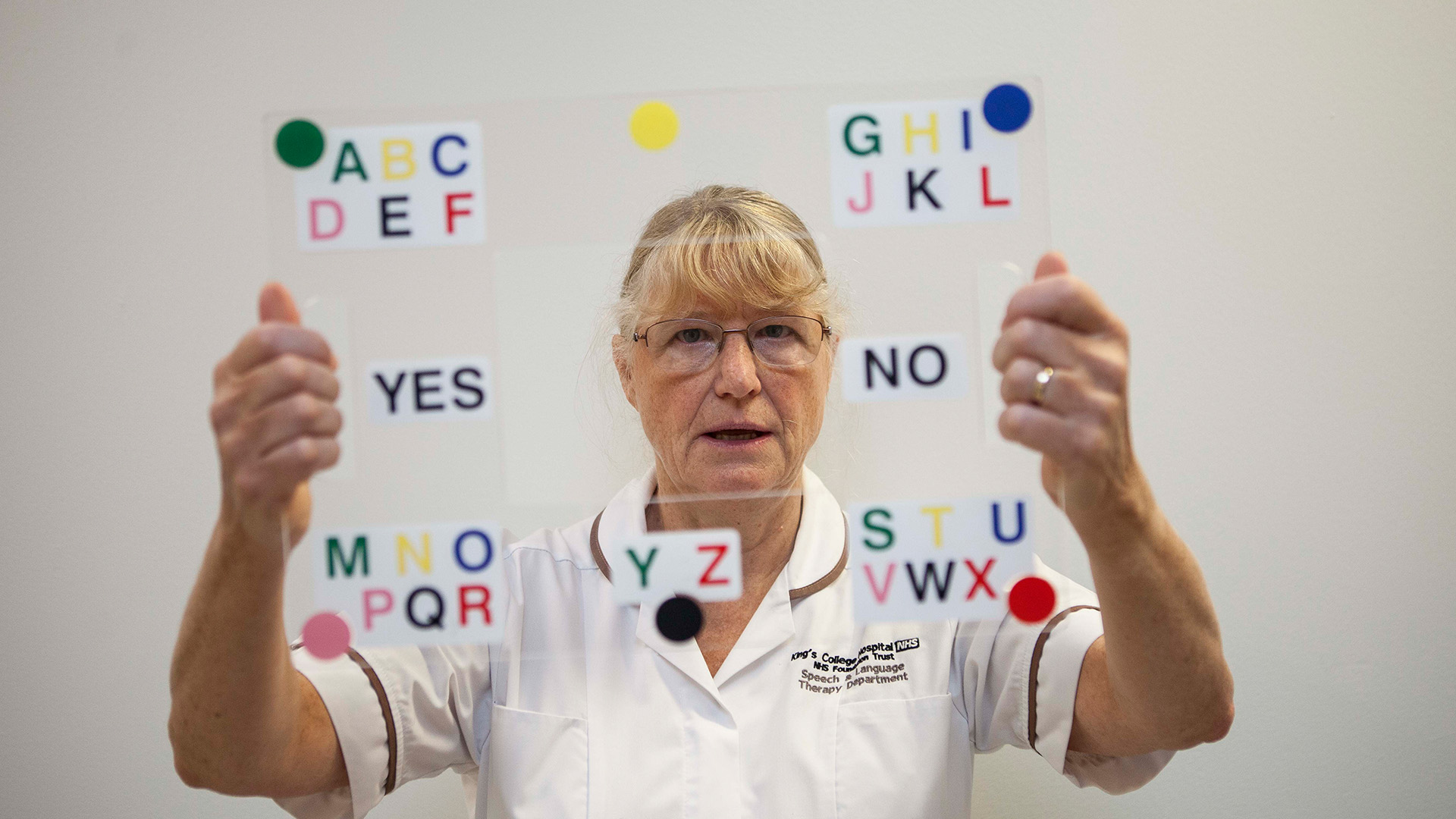

AAC ranges from unaided systems, such as signing and gesture, to aided systems, such as low-tech picture or letter charts, through to complex computer technology. The options can be broadly categorised as:

- low-tech: simple, non-electronic aids such as pen and paper, communication boards/books

- high-tech: computerised devices including voice output communication aids (VOCAs), speech-to-text devices and software for smartphones, tablets and computers.

There is no single best approach to AAC for MND. Most people will benefit from using a range of aids and techniques to support their communication throughout the disease course. A combination of all of the above is often needed, as the most appropriate way of communicating will be very dependent on the communication situation.

Those who choose to use high-tech communication aids benefit from having a low-tech option as a back-up in case of power failure, or a change in their needs that make it difficult to use their high-tech aid. There is also the recognition that one device or system may not work in all situations or environments, so more than one solution may be appropriate.

For more detailed information, see our AAC webpages.

Voice and message banking

Voice banking is a process which allows a person to use a synthetic version of their own voice with an AAC device. In order to bank their voice, the person with MND records a list of phrases with their own voice, while it is strong enough to do so. This recording is converted to create a personal synthetic voice for use with speech-generating communication devices. An infinite number of words and sentences can be generated for when the person is no longer able to use their voice.

People with MND with severe dysarthria may not be able to bank their voice, as sentences need to be pronounced intelligibly as they are recorded. However, some services are able to produce ‘repaired’ synthetic voices by mixing in other recordings or create synthetic voices from scratch. See Information sheet P10 – Voice banking for MND to find out more.

Information about voice banking should be provided as early as possible after diagnosis by the SLT or member of the multidisciplinary team. This needs to be managed sensitively.

If the person with MND decides to bank their voice, the SLT should try to arrange to start the process as soon as possible. If there is no experience of voice banking within the team, advice can be sought from the MND Association. Call MND Connect on 0808 802 6262 or email communicationaids@mndassociation.org

The MND Association will fund the cost of voice banking for any individual living with MND up to a maximum of £500 if self-funding is not possible or desired. Unlike communication aid provision, voice banking is not strictly considered to be funded by NHS services, although there is an expectation that NHS services will assist and support with the process of voice banking or advice.

Message banking

Message banking is a process that allows a person to record particular phrases in their own natural voice that they may say on a regular basis, such as ‘Hello’, ‘My name is....’ or ‘I love you’. It can also be used to record sounds unique to the person, such as their own laugh.

The recorded messages can be organised, stored and played back directly on devices such as smartphones or tablets. There is no limit to the number of phrases a person can record with their natural voice, but this may take time and effort, depending on how the person’s MND affects them.

See Information sheet P10 – Voice banking for MND to find out more.

Page last updated: July 2023

Next review: July 2025